Well, I had to make myself somehow read the never-ending chapters of Concepts of Programming Languages by Robert W. Sebesta.

Everything that follows must be appreciated as bullet points for a quick recap of the material about concurrency, and for deeper knowledge, one should refer to the aforementioned book (Chapter 13). Nevertheless, I made further research on some points that were not clear to me and on some others that I was curious about.

The structure of the article is almost identical to the CPL book. This is the first part of the article dedicated to concurrency, where we will get to understand the concept of concurrency, common multiprocessor architectures (SIMD/MIMD), as well as discuss subprogram-level concurrency. More detailed topics — semaphores, monitors, message passing will be discussed in the second part unless I die.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Multiprocessor Architectures: SIMD & MIMD

- Hidden Concurrency

- Concurrency Categories: Physical & Logical

- Subprogram-Level Concurrency

- Tasks vs Subprograms

- Task Categories: Lightweight & Heavyweight

- Synchronization

- Cooperation Synchronization

- Competition Synchronization

- Scheduler

- Task States

- Liveness and Deadlock

- Language Design for Concurrency

- References & Readings

Introduction

Concurrency in software execution can occur at four different levels:

- Instruction

- Statement

- Unit

- Program

When unit-level concurrency means executing subprogram units simultaneously.

In instruction and program-level concurrency, no design issues are involved, therefore, the chapter in the book doesn’t discuss them. But we will, because we are not the chapter.

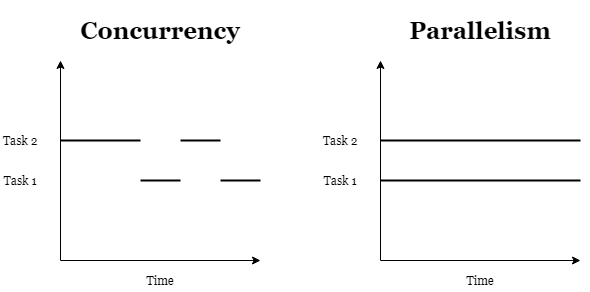

Instruction-level concurrency is a hardware level concurrency. However, considering 5-stage pipelined architecture (5SPA) to be concurrent would not be precise, as parallelism and concurrency must not be confused. The following image should clarify the difference.

In concurrency, we are switching from one task to another without completing the execution, whereas in parallelism tasks are executed at the same time. For this reason, parallelism is not possible with a machine with a single processor, whereas concurrency is.

5SPA can be both parallel (if implemented on a machine with multiple processors) and concurrent. The execution of instruction stages (fetch, decode, etc) are executed concurrently on each cycle by a CPU, in no particular order.

Statement-level concurrency is largely a matter of specifying how data should be distributed over multiple memories and which statements can be executed concurrently (Sebesta). Dr. Gregor Bochmann brings an example of sequential programming languages, such as C or Fortran, when certain optimizers can determine which statements are independent of one another and can be executed concurrently without affecting the result of a program. These optimizers can also take into account the hardware architecture.

Program-level concurrency is when several programs are executed in an interleaved manner in a time-sharing operating system. The overall concept of it is very similar to the subprogram-level concurrency, which will be discussed later in greater detail.

Even though concurrent control mechanisms were originally devised for solving particular problems in operating systems, now they are implemented in various applications (e.g. Web browsers).

While developing concurrent software, one should take into consideration its scalability and portability. A concurrent algorithm is scalable if the speed of its execution increases when more processors are available. The algorithm is portable when software systems can run efficiently on machines with different architectures.

Multiprocessor Architectures: SIMD & MIMD

In 1966, Micheal J. Flynn suggested a categorization of computer architectures based on the number of instruction and data streams.

Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) — Computers with multiple processors, executing the same instructions concurrently, each on different data.

In SIMD computers, processors have their own local memory, one processor controlling the operations in other processors that execute the same instruction set at the same time. Therefore, synchronization is not required.

A special type of machines called vector processors are arguably the most widely used SIMD. If I was you, I’d read the Wikipedia page about SIMD, because I don’t know what I am talking about.

Multiple Instruction, Multiple Data (MIMD) — Computers with multiple processors, operating in an independent and synchronized manner.

Each processor has its own instruction stream. There are two configuration modes of MIMD computers: distributed and shared memory systems. Again, I will refer to the Wikipedia page about MIMD, as the book says a word or two about the configuration models.

Shared-memory MIMD requires synchronization to prevent memory access clashes. Even distributed MIMD computers, which are more common than SIMD computers, support unit-level concurrency.

The chapter’s focus in the book is on language design for shared memory MIMD computers — multiprocessors.

The following article is short and summarizes SIMD & MIMD perfectly: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/difference-between-simd-and-mimd/

Hidden Concurrency

For a long time, there was no need for faster software, as the power of processors has been continually increasing. Two hardware factors provide faster computation: the increasing speed of processor clock rates (every 18 months) and the implementation of several different kinds of concurrency in the processor architecture. That is, pipelining of instructions and data from the memory of the processor, the use of separate lines for instructions and data, prefetching of instructions and data, and parallelism in the execution of arithmetic operations. These are collectively called hidden concurrency.

However, Moore’s law is dead, and the significant increases in the speed of individual processors will no more be possible. Therefore, increasing the number of processors seems to become the only cure for increasing the speed of execution in a program.

Concurrency Categories: Physical & Logical

Two distinct categories. One is physical concurrency, when more than one processor is available and several program units from the same program execute simultaneously with their help. Two is logical concurrency, when the execution of programs is taking place in an interleaved manner on a single processor (i.e. simulation of physical concurrency).

We need a definition for thread of control. In the book, it is defined as “the sequence of program points reached as control flows through the program”. Now you should read the definition again seven more times.

Programs with coroutines and no concurrent subprograms have a single thread of control (despite sometimes being referred to as quasi-concurrent). Multiple threads of control is possible in programs with physical concurrency. A multithreaded program executing on a single-processor machine becomes a virtually multithreaded program (logical concurrency).

Subprogram-Level Concurrency

Tasks are concurrent units of a program (also referred to as processes). Each task can support one thread of control. In Java, for example, certain methods serve as tasks, which are executed in objects called threads.

Tasks vs Subprograms

Unlike subprograms, tasks may be started implicitly. Furthermore, in some cases, programs do not wait for the task to complete its execution before continuing their own. Finally, after the execution of a task, control may or may not return to the unit that started that execution.

Task Categories: Lightweight & Heavyweight

Again, two distinct categories: heavyweight and lightweight. Lightweight tasks run in the same address space, whereas heavyweight tasks execute in their own distinct address spaces. Lightweight tasks are easier to implement and can be more efficient than heavyweight tasks, as their execution demands less effort.

There are three ways that a task can communicate with other tasks: through shared nonlocal variables, through message passing, and through parameters.

Synchronization

Synchronization is a mechanism controlling the order in which tasks execute. There are two kinds of synchronization: cooperation and competition.

Cooperation synchronization is required when task A must wait for task B to complete before task A can begin or continue its execution.

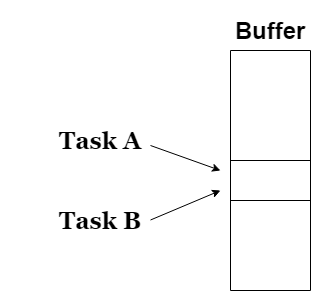

Competition synchronization is required when both task A and B attempt to use the exact same resource at the exact same time when it cannot be simultaneously granted.

Cooperation Synchronization

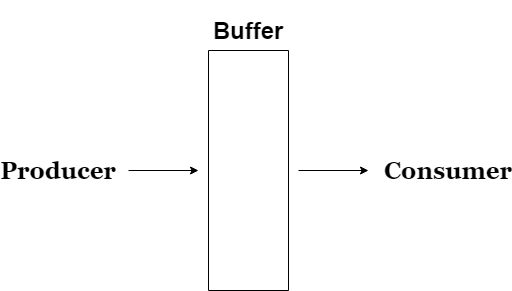

To illustrate a simple form of cooperation synchronization, we must understand the producer-consumer problem.

As illustrated in the image above, the producer produces some data and puts it in the buffer, and the consumer accepts the data. However, the task must be correctly synchronized, as the consumer should not be able to take any data from the buffer if it is empty, and the producer, on its part, should not be able to put any data into the buffer if it is full.

Competition Synchronization

Competition synchronization is achieved by providing mutually exclusive access to the shared data. Race condition is a common issue here, when tasks are competing for a shared resource and the behavior of the program is dependent on the task winning the race.

A common way to solve the racing condition is by providing mutually exclusive access to a shared resource by request. That is, if one of the tasks wants to access the resource, it must request it to check whether another task has it in its possession. If that is the case, the requesting task is not permitted to access the resource and must wait till the task possessing the resource completes its execution.

The following methods can serve that purpose, which we will discuss later in more detail:

- Semaphores

- Monitors

- Message Passing

Scheduler

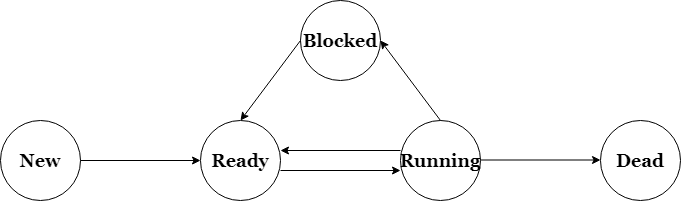

A program called a scheduler manages the sharing of processors among the tasks. To understand the working principle of the scheduler, we must first understand the generalized states that a task can find itself in.

Task States

- New. A task has been created but has not begun its execution.

- Ready. Either a task has not been given processor time by the scheduler, or it was blocked for some reason. Ready tasks are stored in a task-ready queue.

- Running. A currently executing task.

- Blocked. A task’s execution was interrupted for some reason, commonly due to an input or output operation.

- Dead. A task that is not active anymore. It has either completed its execution or explicitly killed by the program.

How a ready task is chosen to the running state can be implemented in different ways (First Come First Serve, Round Robin, etc). The chosen algorithm is implemented in the task scheduler.

Liveness and Deadlock

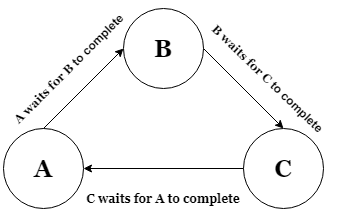

Liveness is when an executing program eventually completes its job. A common way of loss in liveness is called deadlock. In simple terms, task A waits for the resource that task B possesses, and at the same time, task B is waiting for the resource that task A possesses. Thus, both tasks are stuck in a deadlock, never being able to complete their execution.

Language Design for Concurrency

A number of languages support concurrency, beginning with PL/I since the 1960s, up until the contemporary languages Ada 95, Java, C#, F#, Python, Ruby, and Go. It is worth noting that, Python and Ruby, being interpreted languages, only support logical concurrency. Therefore, programs written in the interpreted languages cannot make use of more than one processor, even if the machine had them.