For the first part, click here.

Let’s recall that we should discuss three methods to provide mutually exclusive access to a resource (semaphores, monitors, message passing). However, there are definitely more options. The following links lead to their corresponding Wikipedia pages.

- Locks (mutexes)

- Readers–writer locks

- Recursive locks

- Semaphores

- Monitors

- Message passing

- Tuple space

Table of Contents

Semaphores

In 1965 (or in 1962, or in 1963), famous Dutch computer scientist Edsger W. Dijkstra1 proposed the usage of semaphores as a way of providing exclusive access to shared resources. Semaphore is simply a variable that is used for the synchronization of tasks. It’s a guard, it either allows access or not — just like the green traffic light.

With the help of semaphores, let’s solve the producer-consumer problem that we have discussed in the previous part. As a quick reminder, we have a buffer with limited space, and we should not allow the producer to put any data into it if the buffer is full, and at the same time, not allow the consumer to take any data from it if the buffer is empty.

Initially, we need to understand two important subprograms, called wait and release2 (refer to the notes below for a free Dutch vocabulary lesson).

Wait takes semaphore as a parameter and checks for its value. If the semaphore’s value is greater than zero, then the needed operation can be freely carried out. But before that, the counter value of the semaphore is decremented to make it take note that less space is remaining in the buffer. If the semaphore is zero, the operation is put in the queue.

Let’s take the following example for allegedly easier understanding. Initially, there is room for 10 books (resources) on the shelf (buffer).

We initialize a semaphore called emptyspacesabandonedplaces to 10. If we want to put one book on the shelf, we must check if there is space. Therefore, as we are machine and not human, we run the subprogram wait, and see that our semaphore equals 10. It means there are 10 empty places on the shelf. Before putting the book on the shelf, we decrement the semaphore by 1 to indicate that we will soon have 9 empty spaces.

If the shelf is completely filled with books, our semaphore will be equal to zero (zilch space). In which case, we put the book in the queue (e.g. on the table next to the shelf).

Release subprogram. If there are no books in the queue waiting to be put on the shelf, it increments the semaphore (e.g. there are again 10 empty places on the shelf). If there are books waiting in the queue, then the release subprogram moves one of the books on the table to the task-ready queue (refer to the task states section in Part I for more information). With our analogy, we simply grab the book from the table and hope to put it on the shelf.

Before writing a simplified pseudo-code, we must take into account the competition synchronization. For this, we will use access semaphore for mutually exclusive access to buffer (e.g. two producers will not be able to add items to the empty queue at the same time).

There are a couple of important features to note down about semaphores.

Firstly, two types of semaphores exist: binary and counting. In the above example, we used counting semaphores. A binary semaphore can obviously be 1 or 0 depending on whether a condition is met or not.

Secondly, operations in subprograms must take place atomically. That is, all the operations must be completed in one go with no external interference, as otherwise, subprograms may easily “forget” to increment/decrement semaphores. Atomicity can be achieved on hardware possessing read-modify-write instruction (most computers are provided with it). In the absence of it, a software mutual exclusion algorithm is used.

And lastly, according to Per Brinch Hansen, semaphores are ideal only for ideal programmers who never make mistakes. Indeed, the pseudo-code we have just seen is as simple as it gets. In reality, a programmer must be careful not to forget any relevant steps and must maintain the integrity of a program.

Although, as noted in Wikipedia, even in that case multi-resource deadlock can occur (different resources are managed by different semaphores, and tasks need to use more than one resource simultaneously).

For short stories, always refer to Borges, Maupassant, and Chekhov.

Monitors

As we have some imagination about the shortcomings of semaphores, we can now deal with monitors. In 1971, Edsger Dijkstra suggested the encapsulation of all synchronization operations. After two years, Per Brinch Hansen, whose Wikipedia page we have already read, formalized this idea, and Sir Anthony Hoare defined it as monitors in 1974.

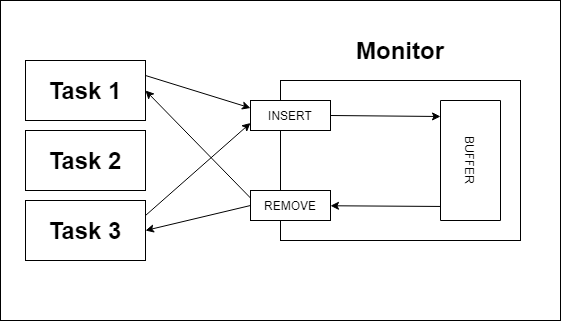

An essential feature of monitors is that shared data is located within the monitor rather than in a client unit. That makes monitors powerful in comparison to semaphores during competition synchronization. However, cooperation synchronization should still be implemented by a programmer, and especially, possible underflow/overflow cases must be taken care of.

Monitor is an abstract data type (ADT).

Different programming languages provide different ways of implementing monitors. In C# we have a predefined Monitor class. Whereas in Java monitors can be implemented in a class designed as an ADT, with the shared data being type. Ada 83 includes a general tasking model to support monitors, whereas Ada 95 has protected objects, when both approaches use message passing to support concurrency (Sebesta). Ada 83 supports only synchronous message passing which we will talk about pretty soon.

The Wikipedia link for Monitor, this time the real one: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monitor_(synchronization)

Message Passing

Couldn’t find any normal painting of Hermes, therefore this.

Message Passing (unrelated to the OOP concept) was developed by Brinch Hansen and Hoare in 1978. Guarded commands are the basis of the construct designed for message passing (Sebesta).

Message Passing can be synchronous or asynchronous. The book of Sebesta talks about synchronous message passing only, so we will begin with that.

In synchronous message passing, busy tasks cannot be interrupted by other units. Here, a task can notify other tasks that it completed its processing and is ready to receive messages. A task can also suspend its execution, either due to being idle or waiting for some expected information from another unit.

When a task waits for a message, and at the same time, another task sends that message, the possible message transmission is called rendezvous (pronounced as “rehn-dez-voh-ooz”). 3 Rendezvous can happen if both parties want it to happen, and it can be transmitted in either one or both directions.

A fantastic explanation of Message Passing can be found at Bartosz Milewski’s blog. Below, for example, is the difference between synchronous and asynchronous message passing taken from the mentioned post.

In the synchronous model, the sender blocks until the receiver picks up the message. The two have to rendezvous.

In the asynchronous model, the sender drops the message and continues with its own business.

After reading the article, I got the impression that the synchronous model is right for the academic explanation, whereas the asynchronous model is more practical. Just like Scheme, as opposed to Common Lisp.

Footnotes

-

If unsure who invented something, say “Dijkstra”. ↩

-

In Edsger Dijkstra’s original paper, he uses V and P as the initials for verhogen, meaning “increase”, and probeer te verlagen, meaning “try to reduce”. English textbooks introduce various translations for that: up and down, signal and wait, release and acquire, post and pend. But as we are obliged to confuse ourselves, we should go with Robert W. Sebesta’s mixed release and wait option. ↩

-

Joking ↩