Go is very neat and its support for concurrency is powerful. So you should not think twice about your language choice when your task is to implement a concurrent image pixelizer. Although conventional threads are supported by Go, doing tasks concurrently is as simple as putting the go keyword at the beginning of a function:

go someFunction() {...}

This lightweight thread of execution is officially called a goroutine, and for a basic overview on goroutines, you can refer to the official go tour (although it is not necessary for understanding this article). There have already been written dozens of other articles about goroutine channels, but the best article on the matter is definitely Anatomy of Channels in Go. I had also stumbled upon an article about image processing in Go, which illustrates the parallel execution of goroutines by creating an image collager.

But what do we want to program this time?

README.md

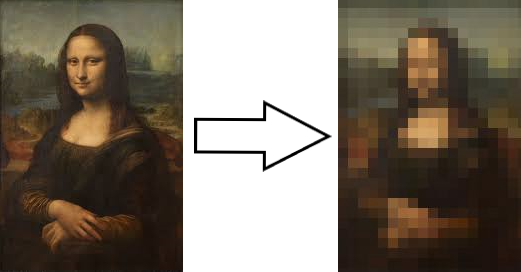

The program reads a .jpg file from the path, after which, from left to right, top to bottom, finds the average color for the (square size) x (square size) boxes. Then it sets the color of the whole square to that average color:

You can call it anything you want — pixelization, censorization, mosaic-maker. Two processing modes will be available for the user:

- Single-threading [S]

- Multi-threading [M]

The application will take three arguments from the command line: file name, square size, and the processing mode. For example:

$ go run main.go somefile.jpg 5 S

After the execution, the result will be stored in the result.jpg file.

If our goal is clear, let’s jump on to discuss the implementation. The full code you will find in the Github repository.

Planning out Concurrent Image Processor in Go

Let’s define in bullet points what we are supposed to do in order to achieve our goal:

- Read an image file

- Create a mask to draw our processed image on

- Step over the original image in pre-defined square-sized steps

- Find the average color of each square

- Draw the resulting color to our mask

- Save the final mask as our result

But there will be lots of finesses along the way, as we are willing to implement our image processor concurrently.

Programming Concurrent Image Processor in Go

The first steps are easy. Let’s create two functions for reading and saving a .jpg file. You can program it in another way to support any other format or formats.

Reading an image file

func openImage(imagePath string) image.Image {

file, _ := os.Open(imagePath)

defer file.Close() // cleanup

img, _, _ := image.Decode(file)

return img

}

Note: I will not specify error checking which is very simple and can be found in the aforementioned repository.

Saving an image file

func saveImage(imagePath string, img image.Image) {

ext := filepath.Ext(imagePath)

dir := filepath.Dir(imagePath)

newImagePath := fmt.Sprintf("%s/result%s", dir, ext)

file, _ := os.Create(newImagePath)

defer file.Close()

jpeg.Encode(file, img, nil)

}

As the codes above are simple and self-explanatory, and as we are interested in the main logic, let’s skip the details here. However, if you are new to programming (not only to the Go programming language), simple googling should clarify the matters.

Iterating over an image

Our next step was to create a mask for the image to draw our result on. However, as we are going to define it in the main function, let’s, for now, assume that we already have a copy of the image called res .

Now we should write a code for our main logic to iterate over the whole image by square-sized steps.

for x := startX; x < sizeX; x = x + squareSize {

for y := startY; y < sizeY; y = y + squareSize {

// process the image

}

}

We can get rid of starting variables by specifying them as 0 , however, as we are going to use goroutines and give them different starting points by modifying the function, we will keep them.

Now we can write the logic for processing an image. We will have to create a temporary mask for finding the average color of each square in the image. For this, we are going to use Go’s image package, which is simple and nice. It is also powerful if your task is only consisting of manipulating rectangles and drawing simple shapes.

Let’s create a mask for each rectangle in the image, find the average of its colors, and then draw the averaged color on our result mask.

temp = image.NewRGBA(image.Rect(x,y, x+squareSize, y+squareSize))

The code above creates a rectangle by defining starting and ending points and then parses it into the RGBA color model.

color = averageColor(x, y, x+squareSize, y+squareSize, res)

This code, on the other hand, finds the average color for each square. We will soon define the logic for the averageColor function.

draw.Draw(res, temp.Bounds(), &image.Uniform{color}, image.Point{x, y}, draw.Src)

Finally, we draw the averaged color into the resulting mask (which we will define in the main function). Let’s connect all the dots to get the whole picture.

func processImage(startX, startY, sizeX, sizeY, squareSize, goroutineIncrement int, res draw.Image) {

var temp image.Image

var color color.Color

for x := startX; x < sizeX; x = x + goroutineIncrement {

for y := startY; y < sizeY; y = y + squareSize {

temp = image.NewRGBA(image.Rect(x, y, x+squareSize, y+squareSize)) // creating a temporary mask for the square

color = averageColor(x, y, x+squareSize, y+squareSize, res) // finding the average color for the square

draw.Draw(res, temp.Bounds(), &image.Uniform{color}, image.Point{x, y}, draw.Src) // setting the color for the square

}

}

}

Note that we also step by squares by thegoroutineIncrement on the x-axis which we are going to define later.

Finding the average color

The following logic is based on the article by Jim Saunders. Although there is a more efficient way of finding the average, a common-sense option is to iterate over a rectangle, put the red colors into the red bucket, the green colors into the green bucket, and the blue colors into the blue bucket (no need to calculate alpha). After which, it is enough to divide each RGB element by the number of pixels and return the color.

const convertRGB = 0x101

const alpha = 255

func averageColor(startX, startY, sizeX, sizeY int, img image.Image) color.Color {

var redBucket, greenBucket, blueBucket uint32

var red, green, blue uint32

var area uint32

area = uint32((sizeX - startX) * (sizeY - startY))

// separating rgba elements and finding each bucket's size

for x := startX; x < sizeX; x++ {

for y := startY; y < sizeY; y++ {

// no need to calculate alpha

red, green, blue, _ = img.At(x, y).RGBA()

redBucket += red

greenBucket += green

blueBucket += blue

}

}

// averaging each bucket

redBucket = redBucket / area

greenBucket = greenBucket / area

blueBucket = blueBucket / area

return color.NRGBA{uint8(redBucket / convertRGB), uint8(greenBucket / convertRGB), uint8(blueBucket / convertRGB), alpha}

}

It’s simple, huh? Let’s finally define our main function, destination mask, and…goroutines.

The main goroutine

One peculiarity of Golang is that its main function is itself a goroutine — the main goroutine. This means that the non-main goroutines are going to execute concurrently with the main goroutine, and there is a chance for the main goroutine to complete its execution before other goroutines. Even though I knew it, still, I was unfamiliar with the usage of wait groups and it took me a while to figure out the correct implementation of goroutines (thanks to the help of stackoverflow).

Let’s declare our variables in the main function.

var wg sync.WaitGroup

var sizeX, sizeY int

var img image.Image

var res *image.RGBA

var goroutineCount int = 1

var goroutineIncrement int

We initialize goroutineCount to 1 as the default mode will be single-threaded.

Then we need to read from the command line and open the image from the given path. readCommandLine function is simple and doesn’t need explanation (again, you can find the full code in the Github repository).

imagePath, squareSize, processingMode := readCommandLine()img = openImage(imagePath)

Let’s get the image size to ease the later usage.

sizeX = img.Bounds().Size().X

sizeY = img.Bounds().Size().Y

Finally, we can define the destination mask. The logic of the code below is the same as in the image processing function when we draw the averaged square on a mask. Simply, the purpose of the code below is to copy the image into the mask.

res = image.NewRGBA(image.Rect(0, 0, sizeX, sizeY))

draw.Draw(res, res.Bounds(), img, image.Point{0, 0}, draw.Src)

Now let’s see how we are going to define the number of goroutines in the case of multi-threading. As we are going to process our image from top to bottom, we need to define the number of goroutines based on the image’s x-axis. That is, if the size of the image is 300 pixels and it is demanded to average 10 pixeled boxes, we are going to have 30 goroutines, one for processing each vertical line.

if processingMode == "M" {

goroutineCount = int(math.Ceil(float64(sizeX) / float64(squareSize)))

}

After knowing our goroutine count, we can add them to the waiting group. The wait group simply takes into account the number of goroutines that the main goroutine needs to wait for.

wg.Add(goroutineCount)

In the end, we need to also define our goroutineIncrement variable to correctly “step” over the image.

goroutineIncrement = goroutineCount * squareSize

Culmination

Finally, attention please, here comes the goroutine implementation. In a for loop, we defer all the goroutines, each starting at square size apart (i*squareSize).

for i := 0; i < goroutineCount; i++ {

go func(i int) {

defer wg.Done()

processImage(i\*squareSize, 0, sizeX, sizeY, squareSize, goroutineIncrement, res)

}

}(i)

We then save the image and make the main goroutine wait for it.

defer saveImage(imagePath, res)

Finally, we force the main goroutine to wait for other goroutines until everything else completes their execution.

wg.Wait()

Future Work

For sure, the program is very simplistic and further optimizations are possible. In case there is a bug that I am not aware of, feel free to point it out or pull requests.